Anishinaabe Migration and History on the Marquette Iron Range

By: April E. Lindala

Director, Center for Native American Studies, Northern Michigan University

Part I - The Migration and the Seven Fires Prophecies

Oral tradition or oral teaching is recognized as a principal form of instruction within Anishinaabe or Ojibwe culture. Through oral traditions we know that the Ojibwe who live near Lake Superior today traveled to the Upper Great Lakes region from the area now known as Newfoundland. Edward Benton Banai, Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Ojibwe, authored a book entitled simply, “The Mishomis Book,” Mishomis meaning grandfather. While this may seem to contradict the idea of oral teachings, Benton-Banai uses the first person voice of “grandfather” to address the reading audience.

Traditional oral histories speak of seven migration stops on this journey. “The Mishomis Book” is compelling in that it carefully guides readers through the seven migration stops of the Anishinaabe as well as the seven fires (or prophecies) of the Anishinaabe. There were seven prophets who instructed the people with seven predictions of what the future would bring. Each of these prophecies was called a Fire and each Fire referred to a particular era of time that would come in the future.” (Benton-Banai 89)

The Ojibwe were instructed to look for “a turtle-shaped island that is linked to the purification of the Earth” (Benton-Banai 89). The prophets further instructed the Ojibwe that they would be stopping at seven specific locations along their journey and that if they didn’t leave they would be destroyed. The prophets continued stating that the “chosen ground” (Benton-Banai 89) would be found when they reached the land where the food grows on the water - manoomin (wild rice). Benton-Banai’s story of the seven fires continues to predict the coming of the “Light-skinned Race.” (Benton-Banai 89). The prophet of the sixth Fire warned of a new sickness and the people would be out of balance. “At the time of these predictions,” Benton-Banai shares, “many people scoffed at the prophets. They then had mush-kee-ki-wi-nun (medicine) to keep away sickness. These were the people who chose to stay behind on the great migration. There people were the first to have contact. They would suffer the most.” (Benton-Banai 90).

It is believed that there were so many Ojibwe that if “one were to climb the highest mountain and look in all directions, they would not be able to see the end of the nation.” (Benton-Banai 94). The Ojibwe used the waterways to travel west by canoe. In the winter they “used sleds and dog teams.” (Benton-Banai 94). It was difficult for many of the Anishinaabe to believe the seven prophets because life was full as they knew it.

Upon their journey from the east, they were instructed to seek a turtle-shaped island. The Ojibwe went through a great search throughout all of the waters to seek this island. “At last, a woman who was carrying a child had a ba-wa-zi-gay-win (a dream) in which she found herself standing on the back of a turtle in the water. The tail of the turtle pointed to the direction of the rising Sun and its head faced the West. The turtle was in a river that ran into the setting Sun. Such an island was found in the St. Lawrence River.” (Benton-Banai 95)

The move from the east took over five hundred years, taking the Anishinaabe through what is now New York, lower Michigan, Ontario and eventually to Moningwunakauning – place of the golden-breasted woodpecker – what is understood today to be near the Red Cliff reservation in Wisconsin. It is the fifth stop that it pivotal to our discussion. The place is known as Bahweting - rapids in a river - known as Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan. Here at this stop, the Ojibwe found the Megis Shell. Benton-Banai writes, “There was a small island here where powerful ceremonies were held. There was so much food in the village that this place came to support many families. Many years later, in the time of the fifth fire, Ba-wa-ting would become a big trading center between the Anishinaabe and the Light-skinned Race.” (100 & 101)

This fifth locale split the migrating Ojibwe into two groups; one group took the northern route over Lake Superior and one group traveled the southern route into what is now known as Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. http://www.ojibwe.org/home/about_anish.html

Part II – Anishinaabe loss of land, language and lifeways.

Prior to European contact we know that the Menominee, the Dakota and the Anishinaabe all considered the Upper Peninsula homelands at one time or another. So the area was already ethnically diverse. Today what we know to be Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, is made up of a rich population of both First Nations people and European immigrants.

First generation European immigrants experienced societal pressures to merge with “American” culture and life ways. Languages, traditions and customs were left behind with the homelands of Europe. However, the primary differences between the Anishinaabe and the immigrant Europeans were that the latter willingly gave up any political rights and privileges. [What is tribal sovereignty? www.airpi.org/pubs/indinsov.html] European immigrants purposefully made the decision to leave their homelands and become part of a new political system. The Anishinaabeg did neither.

Prior to the arrival of European immigrants, the Anishinaabeg occupied millions of acres that now make up the upper Great Lakes region and the province of Ontario at the beginning of the 1800s. Jesuit Missionaries who traveled the region in the seventeenth century kept journals of their encounters with the Anishinaabe and the land of the Upper Peninsula. The first French explorers wrote of Lake Superior in 1618.

The Anishinaabe also had a way of keeping records. “One of the chiefs on Madeline Island kept a special o-za-wa-bik (copper medallion) in his sacred Mide bundle.” (Benton-Banai 103) The medallion was handed down generation to generation. Each time it was handed down a new notch was carved. “In this way a record was kept of the generations of Ojibwe that lived on Madeline Island.” (103)

This copper medallion also has inscriptions that represent various times in history such as the arrival of the light-skinned Race. Eventually, the traders set up a post in the Madeline Island early in the 1800s. A historian, William Warren, spoke to an Ojibwe elder in 1844 who had kept the copper medallion at the time. There were eight notches on the edge of the disc. Benton-Banai speculates, “If we took the lifetime of an Ojibwe in these old days to be 50 years, counting backwards it would put the coming of the news of the Light-sknned Race to this area at 1544 and the settlement of the Ojibwe on Madeline Island at 1394.” (105) Benton-Banai admits that this is a guess, but it gives us an idea of how long the Ojibwe were living in the Upper Peninsula.

The Anishinaabe lived a subsistence based hunter-gatherer lifestyle, moving as small bands to seasonal locales. They “hunted moose, caribou, bear, beaver and some deer; they also fished through the ice and ate stores of dried berries and smoked whitefish during the winter. In the spring, they returned to the south shore of Lake Superior; as the ice went out, they speared sturgeon entering the streams to spawn.” (Ottke 84)

Several factors contributed to the loss of land, language and culture of the Ojibwe. The Muk-a-day-i-ko-na-yayg (black coats) arrived carrying “a cross similar to the representations of the four directions.” (Benton-Banai 106) Some, not all, of these Jesuits felt that the followers of the Midewiwin lodge were involved in devil-worship. “The Black Coats and their Indian converts seemed bent on dividing up the Ojibwe villages into factions.” (Benton-Banai 106)

Just prior to massive immigration, well meaning missionaries and priests converted many Ojibwe people and traditional ideologies began to fade. Legally, Native people living in the United States were not allowed to openly follow traditional ideologies until 1978 with the passing of the American Indian Religious Freedom Act. http://www.nps.gov/history/local-law/FHPL_IndianRelFreAct.pdf

The Anishinaabe ended up settling all around the shores of Lake Superior. Many of the northern villages became part of what is now known as Ontario, Canada. Some Ojibwe even went as far as North Dakota and even Montana (obviously, well past the food that grows on the water). Another damaging factor to the Anishinaabe land, language and culture; the United States government employed policies that forced both removal off of homelands and assimilation into white culture.

Charles Cleland , author of Rites of Conquest: The History and Culture of Michigan’s Native Americans, contends,

“The story of tactics used to separate Indians from their ancestral land holdings and their subsequent concentration on tiny reservations is perhaps the most morally despicable story in North American history. It is also one of the culturally most complex, involving a mix of paternalistic good will, racism, arrogance, and ignorance that is difficult to understand. (198)

Once such instance of arrogance and abuse in the Great Lakes region is the Sandy Lake tragedy, a catastrophic account of how government officials abused power over the Ojibwe. Under President Zachery Taylor’s administration, four officials conspired in the fall of 1850 to trap the Ojibwe in the harsh winter, forcing them to remain at an isolated location in Minnesota. Their goal was to entice the Lake Superior Anishinaabe away from their lands by moving the place of the annual annuity payments to a new temporary sub-agency at Sandy Lake on the east bank of the Mississippi (the usual annuity site was located in LaPointe, Wisconsin). Two of the officials acted out the plan by stalling the delivery of annuity goods and money.

“Without adequate food or shelter, disease and exposure ravaged Ojibwe families. More than 150 died at Sandy Lake from complications caused by dysentery and the measles. A partial annuity payment was finally completed on December 2, providing the Ojibwe with a meager three-day food supply and no cash to buy desperately needed provisions. The following day most of the Ojibwe broke camp, while a few people stayed behind to care for those too ill to travel. With the canoe routes frozen and over a foot of snow on the ground, families walked hundreds of miles to get back home. Another 250 died on that bitter trail, and the Ojibwe vowed never to abandon their villages in Wisconsin and Upper Michigan for Sandy Lake. (“Sandy Lake”)

"Frequently seven or eight died in a day. Coffins could not be procured, and often the body of the deceased was wrapped up in a piece of bark and buried slightly under ground. All over the cleared land graves were to be seen in every direction, for miles distant, from Sandy Lake."

-Rev. John H. Pitezel, Methodist Episcopal missionary

The Sandy Lake Tragedy saw the deaths of four hundred Ojibwe men, women and children. Mikwendaagoziwag – we remember them. (“Sandy Lake”)

The Anishinaabe and the United States entered into several treaty agreements in which the United States purchased land from the Anishinaabe. Property and ownership were viewed differently by each side so “the treaties were understood very differently by the respective signers and often the Anishinaabe believed that, although they had signed a treaty, they had given up none of their most important hunting and gathering privileges on their land.” (Ottke 103) http://clarke.cmich.edu/nativeamericans/treatyrights/washington1836.htm http://clarke.cmich.edu/nativeamericans/treatyrights/lapointe1842.htm

Extraction of the Upper Peninsula’s natural resources - fur trading, mining, and logging – became an attraction for European immigration. More settlers were attracted to the area as a result forcing the Ojibwe off of their homelands.

Marquette had been called “Indian Town” before the entrepreneur Peter White started mining operations in the area in the 1840s. Indian Town lay at the heart of the Great Lakes region. Long before the iron-miners, railroad workers, and canal builders were to turn northern Michigan into the center of an international iron trade, this area was the center of an international fur trade focusing on the beaver. (Feeley-Harnik 237)

Indians were employed wood choppers, ore loaders at the mines in 1880. In that same year wild game animals were scant due to widespread settlement. The Indians were given allotments of forest lands but had way to clear and utilize them.

By the mid-1890s, the Ojibwe in the Upper Peninsula were moved to allotted land reserves “too small to maintain a traditional hunting-gathering-fishing economy” (Bourgeois 14) Many Ojibwe, living in poverty, became dependent upon the local and federal government.

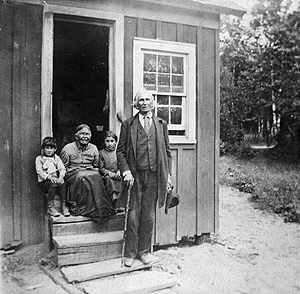

One notable figure from the central Upper Peninsula during this time period is Charles Kawbawgam. Interestingly, Arthur Bourgeois, who compiled several narratives of Kawbawgam, states in his introduction that “Kawbawgam’s chieftainship derived from his claimed succession to Madosh (Kawgayosh), a head chief recognized by the U.S. Government. The fame of his lineage together with his bearing and advanced age reinforced local acclaim to this otherwise landless chief.” (15) Bourgeois further shares that Kawbawgam remained a periodic celebrity in Independence Day parades in Marquette at the turn of the century. (16)

Charles Kawbawgam was born in Sault Ste Marie. However, the south shore of Lake Superior was his home “for some fifty years” (Bourgeois 21) predominantly in the “neighborhood of Iron Bay (Marquette) which was the native section of his wife.” (Bourgeois 21) Charles and Charlotte Kawbawgam were possibly Roman Catholics. However, the pair “spoke no language but their own” and “remained very Indian and Ojibwe in their manner of living and thinking.” (Bourgeois 15)

Kawbawgam and his wife settled north of the mouth of the Carp River in a log house known to the first white settlers as Bawgam House” but also lived for a time at Kawbawgam Lake and along Cherry Creek, Light house Point, upper Chocolay River and on Presque Isle. (Bourgeois 17)

Cleland states that there were some Lake Superior Ojibwe in the mid-1800s who continued to “follow the seasonal round, dressed in a mixture of traditional and American clothing, lived in wigwams and practiced mide’-wi-win and other traditional rituals.” (242) This group of Ojibwe spoke Anishinaabemowin – Ojibwe language – and resisted efforts of missionaries.

They met at Keweenaw Bay each summer and fall to fish and visit their Christian relatives and, when possible, to receive government annuities and subsidies. To the agents and missionaries, the traditionalists represented an obvious illustration of the failure of the civilization programs. It is no wonder they appear so seldom in written account of the reservation – except as a rationale for more appropriations. (Cleland 242)

In 1885 Indian people living along Lake Superior gain their livelihood from working in the lumber and woods industries, berry picking, fishing and limited trapping. It is at this time Indian agent Edward Allen suggests that Michigan Indians be “placed on one large reservation” to be “protected from white encroachment.” Allen further predicts that “the race will disappear in Michigan within fifty years.” (Magnaghi 68)

Between 1885 and 1888, J.D.C. Atkins, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, believed that Indian school children should be speaking English. As he saw it, “To teach Indian school children their native tongue is practically to exclude English, and to prevent them from acquiring it. This language which is good enough for a white man and a black man, ought to be good enough for the red man.” (LeBeau 101) In fact federal policy was composed in 1886 stated that “no books in any Indian language must be used or instruction given in that language.” (LeBeau 101) The solution: remove Indian children from the home.

According to Russell Magnaghi, editor of Indians of Marquette County, in 1885 the majority of Indians on the reservation were able to communicate in English and they even “dress like whites” (68). Although, Kawbawgam reportedly still trapped rabbits and fished, he resided with his wife Charlotte in a home on Presque Isle built by notable Marquette resident Peter White.

Magnaghi’s timeline also states that there were “complaints to the Indian agent over discrimination in the land office over the land selected according to the 1836 treaty.” However, the Indian people were in a complicated situation because they lack of legal expertise.

The policy of assimilation was taking hold in Michigan and in no time, children could not speak with parents or grandparents. In 1887 and 1889, the Catholic Church opened schools in Baraga and in Harbor Springs. The federal government’s Mt. Pleasant Boarding School operated until 1933. In addition to the standard curriculum of reading, writing, grammar, composition, arithmetic, and geography, “Commissioner Thomas J. Morgan in 1889 encouraged Indian schools across the country to teach patriotism.” (Danziger 106)

In twenty-five years, the boarding schools accomplished what armed force, starvation, disease, loss of land, and Christianity could not – a major and irreversible disruption of Indian culture. It also effectively prepared Indian young people, not for assimilation into middle-class America, but as laborers in American fields and factories. (Cleland 245)

This is what the seven prophets predicated as time of the Sixth Fire. “Children taken away from the teachings of the elders. The Indian language and religion were taken from the children. The people starting dying at an early age…they had lost their will to live and their purpose in living.” (Benton-Banai 91)

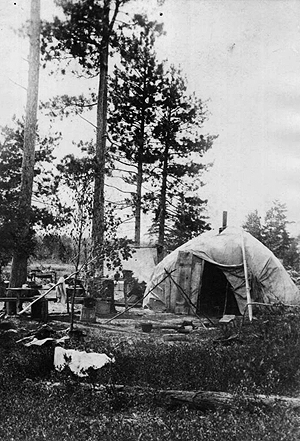

The lifestyle of the Ojibwe had changed drastically. Edmund Danziger states in his book The Chippewas of Lake Superior, that “portable birch-bark wigwams gave way to the one-room log or frame cabins in the late 1890s. Nearly one thousand cabins existed in northern Michigan, northern Wisconsin, northern Minnesota, and 150 in L’Anse.” (104-105)

At the turn of the century, the 850 Chippewas at Keweenaw Bay lived mainly in the towns of Baraga, on the west side, and L’Anse, on the opposite shore. All wore “citizen’s dress,” half held membership in Christian churches, 750 knew enough English for everyday conversation, and 500 could read. (Danziger 107)

On September 11, 1896 a news reporter in the Ashland Daily News sensed the “end of old woodland ways. To celebrate a visit of Buffalo Bill’s show, coaches filled with Ojibwe from nearby reservations arrived in Ashland. “Hundreds of whites flocked to Front Street to see the Chippewas.” (Danziger 109)

Ashland people will probably never again be offered the opportunity of seeing so many Indians who still retain their old customs. The old leaders are yearly passing away, the new generation taking their places are being educated with a view of making them industrious citizens of the United States, and soon the reservations in this vicinity will be converted into flourishing agricultural communities, whose residents will be indeed educated, civilized and progressive citizens of the United States. (Danziger 109)

The policies of assimilation, removal and even in some extreme cases, extermination, were too much. At the turn of the 20th century, number of Native people throughout the United States was at an all time low. In 1900, the Federal Census reported there were 1,873 Indians living in the Upper Peninsula with the largest concentrations in Baraga and Chippewa counties. (Magnaghi 71)

Part III – Cultural Perseverance

Today, the Ojibwe make up the second largest tribal nation in North American with a total of 20 bands in the United States scattered from Michigan to Montana and over 130 bands from western Quebec to eastern British Columbia in Canada.

There are four Ojibwe communities, all with federal recognition [www.ncai.org/Federal_Recognition.70.0.html], located in the Upper Peninsula: Bahweting (Sault Ste Marie), Ketegitigaaning (Lac Vieux Desert near Watersmeet), Gnoozhekaaning (Bay Mills), and Gichi-wiikwedong (Keweenaw Bay). A fifth reservation community exists just west of Escanaba and is home to the Potawatomi of the Hannahville Indian Community.

Cultural perseverance and Anishinaabe language preservation is foremost on the minds of today’s tribal leaders (elected or recognized). This is what Benton-Banai identifies as the Seventh Fire. “The prophet of the Seventh Fire of the Ojibway spoke of an Osh-ki-bi-ma-di-zeeg (New People) that would emerge to retrace their steps to find what was left by the trail.” (111)

Many believe that our people of today are those New People as more and more the young are seeking wisdom from elders who still have knowledge, who have not forgotten the old ways. It is believed that if the New People “remain strong in their quest, the Waterdrum of the Midewiwin lodge will again sound its voice. There will be a rebirth of the Anishinaabe nation.” (Benton-Banai 93)