Immigrants from Cornwall, Great Britian, in Marquette County

By: Russell M. Magnaghi

Background

The British Isles sent thousands of native sons and daughters to Michigan and Marquette County.

When we speak of the British Isle we are actually talking about specific areas such as England,

Scotland, and Cornwall. We find people from these areas appearing in Marquette County from the

earliest days. One of the problems when dealing with the various English groups is that some appear

and some do not appear in various censuses. The English, Scots and Welsh will be listed at various

times but never the Cornish. As a result you have to master the key to Cornish surnames and then

you can identify Cornishmen. The other technique you can use to focus in on Cornishmen is to figure

since they are usually involved in mining areas where mining is important such as Negaunee and

Ishpeming will be the centers of Cornish concentration. Unfortunately this is neither a scientific

nor accurate way of counting Cornishmen.

It was not until the reign of Elizabeth I in the late 1500s that England began to develop as a

unified and nation growing in power. It was the natural resources and subsequent industrialization

that brought prosperity to the British Isles. Despites these developments, there were many people who

left the nation due to poverty, economic downturns, religious problems and political concerns. Many

Englishmen made their way to Michigan seeking employment. For many of them Canada was the primary

point of entry into the United States. Often these immigrants were single men who left England with

the hope of developing a fortunate in the United States. However very quickly most of them married

upon settling in the state.

The Cornish people who haled from the southwest peninsula of Cornwall, where tin and copper mining

had been conducted for thousands of years, were naturally attracted to the mines of Marquette County.

The Scots had their problems with the English, but they were aggressive businessmen and many of them

left for better opportunity in the United States. There were also many Englishmen who had similar reasons

for leaving their homeland. Although these early immigrants spoke the language of their new nation, they

were usually bewildered by the new land, society and even the language which was American and not exactly

English. They gingerly worked through the various obstacles they encountered.

An English Overview

In this study we will be studying the English in general and then we will move into specific studies

of the Cornish, Scots, Welsh, and Manxmen. The first Englishmen to visit Marquette County would have been

English fur traders like Alexander Henry who passed along the coast in the years after 1760. The usual

camp site along the coast was at Little Presque Isle as the canoe men would traverse from Shot Point the

former location and avoid a lengthy detour into Marquette Harbor. There was talk of Henry bringing some

Cornish miners to help exploit copper and iron deposits. However this is speculation as there is no hard

evidence available. In the late eighteenth century, when Englishmen especially Scots traveled to their

important fur trading center at the western end of Lake Superior at Grand Portage and later at Old Fort

William at modern Thunder Bay, Ontario, they followed the northern shoreline of Lake Superior, but some

traders might have made the trip along the south shore as well.

It is difficult to accurately utilize the Federal census to identify and count Englishmen in the Upper

Peninsula and Marquette County. Depending on the census, “English” could mean all Englishmen while others

will identify “Scots, Welsh and Irish.” The people from Cornwall were never identified as such and thus

you must rely on the history of a community and whether or not Cornish people were part of the community’s

development. Then there were others from Devon, the neighboring county of Cornwall to the east. Since Devon’s

history was closely associated with that of Cornwall, numerous immigrants from Devon came to Michigan primarily

to work in the mines. There is no systematic way of identifying these people. You must rely on chance obituaries,

a stray article, or check Alvah Sawyer’s History of Northern Michigan and you will find a few prominent Devonians listed.

When the opening of the Marquette Iron Range after the fall of 1844, we hear of Cornish miners hired to work

a hoped-for silver deposit at Marquette’s Presque Isle Park. There were few Cornish miners on the Marquette

Range prior to the 1870s because mining was done from open pits and the Cornish miners were only interested in

underground mining. In the earliest census of 1850 and 1860 there are a number of Englishmen listed at the

various Marquette Range communities involved in a wide variety of occupations.

Population & Occupations, 1910

Why use the date of 1910? This is considered the high-water mark of immigration. In 1924 restrictive would be

passed which cut into southern and eastern European immigration to the United States, but after that time national

conditions changed and many stayed home rather than leave for the unknown. Also in Michigan by the census of 1920

the booming automobile industry is attracting many immigrants from the Upper Peninsula to Detroit. A final note:

I have concentrated on the five wards of Marquette because fewer Cornishmen settle in Marquette than in the mining

communities of the Range. As a result even if there are a few Cornishmen living in Marquette, this will provide us

with some insight into the occupations of Englishmen in a portion of the county.

In the spring of 1910 there were 194 Englishmen living in Marquette’s five wards. They were evenly divided throughout

all of the wards except Ward 2 with only eight Englishmen. Their occupations and conditions were quite varied in Marquette city.

OCCUPATIONS OF ENGLISH IMMIGRANMTS IN MARQUETTE CITY, 1910

| Architect | 1 | Machinist | 1 |

| Blacksmith | 1 | Merchant | 2 |

| Boarding House Keeper | 2 | “None” married, widows, children | 83 |

| Boilermaker | 1 | Nurse | 2 |

| Bookkeeper | 2 | Ore Boat Sailor | 1 |

| Carpenter | 4 | Own Income/retired | 16 |

| City Clerk | 1 | Painter | 2 |

| Clerk | 4 | Piano Agent | 1 |

| Coachman | 2 | Plumber | 1 |

| Contractor | 1 | Poor House (County) | 1 |

| Cook | 1 | Porter | 1 |

| Dock Worker | 1 | President (Northern State Normal School) | 1 |

| Electrician | 1 | Post Office Worker | 1 |

| Fisherman | 2 | Prison (Marquette Branch Prison) | 2 |

| Furnace man | 4 | Railroad Workers | 15 |

| Gardener | 2 | Salesman | 1 |

| Hotel Keeper | 1 | Sawmill Worker | 1 |

| Insurance Agent | 2 | Servant | 4 |

| Janitor | 2 | Sign Painter | 1 |

| Laborer | 6 | Teacher | 1 |

| Laundryman | 2 | Teamster | 1 |

| Lighthouse Keeper | 1 | Telephone Company | 1 |

| Lumber Camp Worker | 1 | Vessel (Travel) Agent | 1 |

Having completed a review of this table it is obvious that these English-speaking immigrants were able

to go into many occupations that demanded an education and knowledge of the English language. There were

also a number of them who had gained access to government positions such as lighthouse keeper of the

National Life Saving Office, U.S. postal worker, Marquette city clerk, and president of Northern State

Normal School. Other position such as nurse, insurance and travel agents, and architect were occupations

demanding special education and possibly state certification. Others were businessmen and women who needed

not only expertise in their field but also the capital to get the business started.

The Englishmen found a certain amount of fraternal security and solace at the Order of the Sons of St. George.

This organization had been established in Scranton, Pennsylvania around 1875. It quickly spread across the

United States and there were numerous chapters in Negaunee, Ishpeming and Marquette. The clubs played league

cricket, watched Cornish wrestling, and usually celebrated St. George’s Day, April 23. All of these groups

celebrated the 4th of July in grand style.

The various English groups went their spate ways in terms of religion. The English usually became members of

the Episcopal Church, while the Welsh and Scots joined the Presbyterian Church and the Cornish were staunch

Methodists. The latter were excellent singers and were known for their ability at religious services.

Prominent Englishmen

There were two outstanding Englishmen connected with Marquette County that can be discussed at some length. The

first was James H. Bancroft Kaye (1862-1932) who was second president of Northern (1904-1923) and also served as

professor of philosophy and education.[1] He was married to Ina L. Tracey (1893) of Custer, Michigan they had two

children: John Tracey who became a physician and Mildred (Richard Beldsoe). Kaye, who was born in Farnsworth,

Lancashire, England was educated there and came to the United States in 1883.

His father, John B. Kaye was deeply involved in the slavery controversy in America, which caused him to emigrate.

He was a personal friend of Lord Tennyson and Charles Dickens and gave his son a rich heritage of personal and

cultural associations.

President Kaye attended the University of Michigan where he was an instructor and fellow until he received his

bachelor of arts degree in 1892. Kaye received his masters of arts degree in 1912 from Albion College. While

he finished his master requirements, he was an assistant instructor at Albion College.

Prior to coming to Northern, Kaye served in a number of educational capacities around the state. He taught in

the public schools of Custer, Chase, and Ludington, Michigan. From 1892 to 1896, he was superintendent of schools

in Reed City and superintendent in Cadillac from 1896 to 1904.

In July 1904, he became the second principal and later president of Northern State Normal School. Kaye proved to be

an able leader. During his eighteen year tenure as head of Northern, the longest in the history of the institution,

he oversaw the completion of the first physical plant and expansion of the campus. Annexes were constructed and by

1908-1909 a new steam heating plant was in operation. As early as 1912 President Kaye was promoting the completion

of the physical complex as envisioned by Architect D. F. Charleton in 1899. In the summer of 1915, Kaye Hall, which

was dedicated to him in 1949, was opened for use. He was also responsible for the development of the first athletic

field on campus to the west of Kaye Hall in front of the present University Center.

President Kaye traveled around the Upper Peninsula and met with the people. Often he went on commencement trips

where he gave two or three commencement addresses in as many days. His devotion and unselfish service to the institution

gained him a host of friends and admirers throughout the region.

During his presidency student enrollments went from 284 in 1904 to 563 in 1923. Academics were important to him, but

he was also concerned about the social and moral well-being of the students. He implemented many rules and regulations

which were mandated by the State Board of Education.

His administration saw Northern go from a teacher's training school to a college. In 1918 the institution was allowed

to grant the bachelor of arts degree. As a result of this action, students came to Northern to pursue a four-year degree

as well. In 1927, after he was out of office, the State Board of Education re-titled the institution as Northern State

Teachers College to better identify the institution that he had worked so hard to expand.

On December 11, 1922, President Kaye announced to the Faculty Council, that due to poor health he planned on retiring

on July 1, 1923. After his retirement, Kaye gained emeritus status and continued to teach at Northern for an additional

nine years. He taught philosophy and education. He and his family spent the summers in Custer or at his country home at

Scottville, seven miles east of Ludington, and returned to Marquette for classes in the winter.

President Kaye was a scholar who was interested in philosophy and the problem of human conduct and human relationships.

He published numerous articles on the subject of education. He was also an omnivorous reader and developed a wealth of

diverse knowledge. Kaye was a literary scholar who read widely in Latin, Greek, Old German and Anglo Saxon. He was an

authority on Tennyson and Dickens and corresponded with a host of contemporary scholars.

His memberships included the National Education Association, National Society for the Scientific Study of Education,

Michigan State Teachers Association (servedas secretary and vice president), Northern Michigan Teachers Association

(secretary and president), Upper Peninsula Educational Association, National Institute of Social Sciences (executive council),

and the National Economic League (1929). Fraternally he was a Knight Templar and a 32nd Degree Mason.

During his later years Kaye became involved with Rotary International and its program for world understanding and the

betterment of conditions for handicapped children. He was elected governor of the Fifteenth Rotary District at Wausau,

Wisconsin in 1920 and during his year in office became affectionately known as "Governor Jim."

James Kaye was described as having a pleasant personality with a generous and sympathetic heart. His friends knew him

for his love, devotion and unselfish service. Both the city of Marquette and the University have memorialized him. In

1925 the City Commission renamed Hematite Street, bordering the southern boundary of campus after him. In June 1949

the original administration building was named in his honor. After the building was demolished, in 1979 the new president's

residence was named Kaye House by the Board of Control. (Mining Journal 07/12/1932; Ludington Daily News 07/11/1932).

The second prominent Englishman was D. Frederick Charlton[2] who was born May 9, 1856 in West Bank, Wrotham, Kent, England

and died in Marquette in January 1941. He went to Canada in 1884 where he started a small manufacturing plant. In 1886 he

moved to Detroit where he joined a firm of English-born architects and in 1887 married Alice H. Grylls of Cornish ancestry.

Over a period of thirty years, as a member of the architectural firm of Charlton and Kuenzli, he had charge of the designing

of many public buildings and private residences in the Upper Peninsula. He was sent to Marquette by his Detroit firm in 1888

to supervise construction of the Marquette Branch Prison and decided to make his home in Marquette after completion of that

work. Some years later Charlton and E.O. Kuenzli formed a partnership that existed until the former’s retirement in 1917.

Charlton is credited with introducing several radical changes into the designing of large buildings, among which was the

flat type roof, which, although regarded skeptically at first, later became standard. Among the Marquette buildings designed

by his firm were a number which have since disappeared from the scene due to fire or demolition. These include: the Marquette

Opera House, buildings at Northern Michigan University, the county court house (still standing) , and the interior furnishings

of St. Peter cathedral. Charlton had designed the Longyear mansion on Arch Street and oversaw its removal from Marquette to

Brookline, Massachusetts.

After his retirement in 1917 Charlton pursued his hobby photography and developed a skill that was widely recognized. He was

one of the pioneers in the introduction of color and speed photography and examples of his Lumiere plates were shown in

exhibitions throughout Michigan. While he operated his shop in the Harlow Block as a photo-engraver, he continued to work

for a short time as consulting architect. He closed his photography shop in 1937. This immigrant had a very successful career

in Marquette by the time he passed away in 1941.

Cornish[3]

To people away from the Upper Peninsula the term “Cornish” means little to them. However to the history and development

of the Upper Peninsula and Marquette County, in particular, the role of Cornish immigrants is outstanding. But, where

is Cornwall and why were Cornishmen so involved with mining?

Cornwall is the peninsula the size of Marquette County extending away from England to the southwest into the Atlantic

Ocean. Tin and copper have been mined in this county since centuries before Christ and the Bronze Age was stimulated by

minerals from this region. As a result Cornishmen became known as expert miners and mine managers or captains. Legend has

it that St. Piran visited Cornwall and brought Christianity around the 5th century. At one point he built a fire and the

tin melt on the black soil in the form of a cross. The flag with a black background and a white cross is the internationally

recognized flag of St. Piran. By the way, many Cornishmen in the Lower Peninsula celebrated St. Piran’s day on March 5th

with a pasty and saffron bun feast.

Cornish Miners in the Upper Peninsula

As Cornwall was experiencing its mining problems, competition was developing in the Midwest. In the nineteenth century

lead mining developed in the tri-state area of Illinois, Iowa, and Wisconsin, resulting in the need for expert miners.

Mineral Point, Wisconsin, was established as a lead mining community in 1827 and Cornish deep rock miners began to arrive

by the hundreds. By the time Douglass Houghton promoted the fact of copper on the Keweenaw Peninsula in the 1840s; Cornish

miners were beginning to be well-established in the area.

When news of copper fever in Michigan spread to Wisconsin and the coal mines of Pennsylvania and other mining regions,

Cornish people began to migrate. From southwestern Wisconsin they migrated northward by way of the Mississippi, St. Croix,

and Brulé Rivers to the shore of Lake Superior. They traveled through wilderness and battled gnats, black flies, and

mosquitoes. Others traveled by land and lake from Pennsylvania and other eastern communities, and from Canada, especially

from Bruce Mine in Ontario, to reach upper Michigan.

New arrivals from Cornwall and elsewhere in the world were attracted by chain migration - letters and publicity of the

new region to Cornish communities. As early as the summer of 1845 Cornish miners in the Copper Country wrote to the London

Miners' Journal extolling the richness and excellent prospects of the newly opened copper mines in Michigan. Thus

information was picked up by mining interests in Cornwall and elsewhere. The Cornish miners often discussed the value of

these mines with the editor of the Lake Superior News, John Ingersoll, who noted this in his newspapers. This news was

in turn picked up other newspapers in the United States and the news continued to spread. The fact that Cornish miners

gave their nod to the value of these mines was reassuring to the local developers in the Copper Country.

The prosperity of America in general and specifically of the mining industry in America allowed many Cornish people to

send letters to family and friends in the Old Country, where conditions were poor. They also sent money or prepaid tickets

to the Old Country to bring their friends and relatives to America. The Marquette Mining Journal noted in the summer of

1887 that the English of Ishpeming had sent home large accounts of money through banks and post offices.

The first known Cornish miners in Marquette County appeared along the shore at modern Presque Isle Park in the summer of

1845. At that time a group of Cornish miners was observed digging a shaft for possible silver mine at Marquette's Presque

Isle for the Lake Superior and New York Mining Company. Nothing came of this development, but it is important to note that

the first miners were Cornishmen who were known for their expert mining knowledge.

The federal census of 1850 provides some insights into these new immigrants and it is best to review the Upper Peninsula

and then fit Marquette County into the larger story that is unfolding in mid-century. However while they were chiefly from

Cornwall, the census listed them as "English," so speculation about the Cornish is necessary. At the time there were five

Upper Peninsula counties — Chippewa, Michilimackinac, Marquette, Houghton, and Ontonagon. In the non-mining counties of

Chippewa and Michilimackinac there was a small number of Englishmen involved in diverse occupations. It was a different

story in the Copper Country. In Houghton County there were a total of 501 foreign-born residents. Of that number 261

(fifty-two percent) were listed as "English." Their occupations included 122 miners and fifteen laborers. There were thirty

German miners out of 142 and eighteen Irish miners out of fifty-nine compatriots. There were 251 immigrants in Ontonagon

County, of which sixty-one were of English origin. Of that number thirty-three were listed as miners. The next largest

number of miners was twenty-eight Irish followed by six Germans. From these incomplete records we can infer that these

English miners were most likely of Cornish origin. There were fewer of them in the Marquette Iron Range in the 1840s

because they disdained the open pit operations and wanted to work underground.

Cornish Communities in the Upper Peninsula

For many Cornish immigrants, life in this community was their introduction to American life. The immigrants boarded,

rented, or owned their homes, and used their extra money to donate to church and schools, playing a major part in the

community. In the process they assimilated but maintained their heritage as well. The Methodist Episcopal church was

both a religious and cultural center for the community.

Within the mining communities of the Upper Peninsula, people usually lived in clusters of houses located near a

mine shaft so that workers lived where they worked. Within these locations groups of ethnic people tended to congregate

although many became mixed over the years.

Given the fact that many of the Cornishmen were mine captains and managers, their residences were connected with

those of the mine officials. For instance, in Negaunee, the best residences were located on Main Street, where the

wealthier people lived—the mining engineers, superintendents and other salaried mine employees. However, the Cornish

mining families following the general pattern of living in mining locations. A vigorous location in Negaunee was known

as Cornishtown. Originally the men living there worked in the Jackson Mine. Their houses were small cottages. Many

added a garage added with the coming of the automobile, and these garages were at times larger than the original

house. The surrounding hills provided a good garden and hay land. Some families owned cows which grazed on the hillsides

and were kept in small barns during the winter. Mining families this favored location because it was close to the

downtown area and was on the main highway to Ishpeming where many men found jobs as the mines closed in Negaunee.

Iron Ranges

There are three iron ranges in Michigan: the Marquette, Menominee, and Gogebic Iron Ranges. The first mining on the Marquette Range began in 1844. The greatest Cornish immigration to the Marquette Range took place between 1856 and 1885, but especially after 1874 with the sinking of the first shafts and the development of underground mining. Prior to this time, Cornish miners tended to avoid the Marquette Range because ore was mined by the open pit system and this was not traditional mining for them. After shafts were sunk, Cornish miners were attracted to the range and came from other areas like the Copper Country or directly from the Old Country.

Between 1880 and 1890 the introduction of mining machines and the steam shovel (1889) changed conditions around the mines. A labor strike in 1895 drove many Cornishmen and others from the range to mines in Montana, Colorado, and Nevada. In a report issued by an anonymous mining company on the Marquette Range in 1898, the Cornish comprised 25 percent of the employees, while by 1909 their number had been reduced to 13.5 percent. There were also fewer Cornish immigrants leaving the Old Country. The Cornishmen who remained in the mines were those who held skilled positions or were employed as foremen, as managers, or in some other executive capacity.

Although Cornish miners arrived early in the development of the mines on the Marquette Range and many had left by 1890, others continued to be attracted to the range. Chain migration caused many Cornish miners who came from places like Redruth and Camborne migrated to settle in Negaunee to work in the iron mines early in the twentieth century.

Mining Techniques and Equipment

Cornish miners brought with them expertise, lore, techniques, and tools related to mining. As a result they had a great impact on Michigan and American mining. The Cornish made the best mining captains. The mine captain's job was to observe and study the progress of the mine's workings; a mine captain was almost by intuition was able to follow the crazy convolutions of the rock formations and ore bodies. Mine captains took pride in getting the ore out with the least expense, avoiding taking out waste rock, and protecting the safety of the miners under their charge. Although they were trained in colleges as mining engineers, experienced geologists knew to follow directions of the Cornish captains regarding the location, nature and position of ore bodies. The miners held the captains in high esteem and when a captain entered a drift, the men would stop work to show their deference. On the surface the miners would touch their caps and address them as "captain."

Over the course of years, a few Cornish captains owned and operated their own mines. The Negaunee Mine located to the southeast of Negaunee was a small-scale operation developed by Captain Samuel Mitchell in 1887. It was eventually incorporated into the Cleveland Cliffs operation.

The captains contributed their expertise to improve mining methods. Captain Collick was known for his invention of the Cleveland-Cliffs Sheet-Iron Sconce (Cornish for candlestick), a device for shielding the candle flame on the miner's cap. Other Cornish miners on the Marquette Range became famous for their physical strength, their ability to wrestle (see later), handle a drill, or load more ore than others in the mine.

They also introduced "Cornish stamps," a simple but widely used milling technology for crushing ores. Consisting of iron-shod wooden hammers mounted on wooden shafts, which were raised by water or steam power and then dropped, the Cornish mill was well suited to small mines and isolated areas where expensive machinery could not easily be imported. Improvements made upon the Cornish stamp eventually led, by the 1860s, to the growing adoption of the steam-powered stamp, which used all-iron hammers and shafts and steam-pressure rather than gravity for the crushing stroke.

Cornish engineers developed an efficient and reliable modification of the Watt steam-powered pumping engine in the early 19th century especially for mining purposes. Called the Cornish pump, it had found wide use in the Lake Superior mining districts by the end of the 1860s. The reciprocal motion of the steam engine could also be used for other purposes. As mines in the copper districts of the Upper Peninsula began to go hundreds of feet below the earth's surface, conventional ladders became increasingly troublesome as a means of going to and coming from working areas. This led some mines to install another Cornish mining technology: the man engine. Similar to an escalator, a man engine had small platforms mounted six to eight feet apart on a shaft which a steam engine moved up and down. By alternately moving from one of these platforms to stationary platforms mounted on the side of a mine shaft (or to a second parallel moving shaft with similar platforms), miners could move to and from subterranean working areas much more quickly and be better rested than by using ladders.

A question to be answered was whether the miner should be paid for the tonnage or footage removed? The Cornish stoping contract allowed each miner to contract with the mine captain for the work he had to do. This was based on the footage of ore removed. Coming from a sea bound peninsula, the Cornish miners used the term, cubic fathom (six feet) as the basic amount to be removed. The concept was introduced in the 1850s and persisted for 65 to 70 years in many mines. Although the fathom was more or less vaguely interpreted, the contract was generally based on footage drilled per shift, each shift being an individual contract of material removed by an individual. By this system the holes were directed to best advantage under the strict supervision of mine captains. This system allowed more ore than rock to be removed from the mine.

Other innovations included drilling by hand with sledges, blasting with black powder and later dynamite, and hauling a Cornish "kibble," powdered by a Cornish horse-drawn whim were introduced.

The process of extracting the metal from the veinstone was introduced to Calumet and Hecla by Captain Jennings, from the tin mines of Cornwall. The copper of Cornwall, being chiefly in the form of the sulphuret, was obtained by a different process. Sixty tons of veinstones were stamped per week.

Cornish immigrants also introduced medical services. Owners of the Cliff Mine first imported the "bal" surgeon system from Cornwall. In return for $1.00 from married men and 50c from bachelors, the company agreed to have its surgeon look after the men and their families. This practice became widespread through the mining region. Cornish miners have been credited with spurring the creation of the Calumet & Hecla Hospital in 1870.

Cornish Migration Around and Out of Michigan

A little known and understood aspect of life in nineteenth- century America was the ongoing movement of people around the country, and immigrants were no exception. If the Cornish migrated from Wisconsin's lead mines and the coal fields of Pennsylvania to Michigan, what was to keep them in Michigan?

From the earliest days Cornish miners found that with their expertise they could find better positions in developing mining areas throughout the country and the world. As early as 1863 miners from Clifton were leaving for California, Pike's Peak in Colorado, and South America. At other times the loss of jobs or reduction of wages caused many to leave. Although it is difficult to get a head count of men leaving, in July 1892, the Marquette Mining Journal provided a measure. In June the South Shore Railroad in Ishpeming sold more than $600 worth of tickets per day, while in the first week of July, during a downturn, they sold more than $4,000 in tickets.

Within Michigan the record shows that Cornishmen moved to other mining districts. In the Upper Peninsula, as the iron ranges of Menominee and Gogebic opened in the 1880s, Cornishmen from the established areas moved there. During the nineteenth century the great bituminous coal basin in the central part of the Lower Peninsula was gradually developed. The great impetus to the Saginaw coal mining dated from 1895 and was stimulated by the decline of the timber industry, which provided fuel for the extraction of salt. Mines were developed in Bay and Genesee counties to the north and south. The pillar and chamber system of mining was practically the only one used. The labor force came from various districts and more than half of them were Americans and those not native-born had lived an average of sixteen years in the United States. Some Cornish miners found their way to these mines. One of them, Thomas Pengilley, worked in the area during the heyday of coal mining from 1903 until 1922. The coal mines flourished into the 1920s but the poor quality coal caused the industry to go into a slump and many of these miners moved south to Flint and Detroit.

Cornishmen also found mining positions outside of Michigan. They migrated to the iron ranges in northern Minnesota and found positions in the mines and mills of Anaconda and Butte, Montana; others migrated to California. Cornish people dominated Grass Valley and there was a large Cornish community working the silver mines of Virginia City, Nevada. Others moved from the copper mines of Arizona to Utah or from the coal mines of Alabama back to Michigan. Besides the mines in the United States, there was also a demand in Canada, Mexico, Brazil, Chile, and South Africa. Newspaper accounts in Michigan provide a scattered but interesting account of these migrating Cornishmen.

A review of the Marquette Mining Journal illustrates this internal migration. Edward Moyle, an early settler in Negaunee and one of the early employees of the Jackson mine, moved to Butte, Montana, in 1890. Ben Williams left Negaunee in 1894 for Lead, South Dakota, and in the spring of 1905 James and his son William Tonkin migrated to Austin, Nevada, where James' brother, William was located and secured jobs for them. At the time there were other men in Negaunee who were talking of going to the Silver State.

If the immigrants did not migrate from Michigan over the years their children certainly did. When Cornish immigrant Captain Thomas Buzzo died in August 1913, his family was scattered across the United State and Canada. The Minnesota iron ranges had attracted his son Arthur, a mining captain, to Ely, and a married daughter to neighboring Virginia, Minnesota. Two other sons lived in Salt Lake City and Chicago. Two other married daughters and one single daughter lived in Ishpeming, while another resided in British Columbia. The copper city of Butte, Montana, attracted two married daughters. This type of internal migration was common not only to Cornish people but to immigrants of many nationalities.

Jobs were not the only reason Cornish people migrated. There are many accounts of Cornishmen returning to the Old Country in the late 1890 to spend anywhere from two to four months visiting family and friends and enjoying the more moderate climate of Cornwall. Within the United States many people traveled by train to visit family and friends throughout Michigan and in other states regularly. Others found industrial positions in milling and smelting on the East Coast.

Labor

Cornish miners were always seen as an independent group of rugged individualists who worked for the company. The stoping contract, introduced by the Cornish, was a system whereby each miner contracted with his mine captain for the work he had to do. Given their expertise in mining and the fact that many of them were mine bosses, superintendents, and managers, they were not attracted to radical union groups. However, throughout the nineteenth century there were many instances where Cornish miners or their bosses went on strike because of low or unpaid wages, brutal bosses, or poor working conditions. These were usually isolated cases.

Non-Mining Occupations

Without going into all of the occupations that the Cornish went into other than mining it is fair to note that when and where possible they started their own businesses. The Lutey family came from gardening folk in the Old Country and when they came to Michigan they carried on the tradition as florists. They had shops in both Ishpeming and Marquette where the name is still associated with flowers. William Trebilcock in 1909 was a major concrete contractor in Ishpeming and did extensive work for the city on streets, sidewalks, and structures. A study of the 1910 Federal census for Negaunee and Ishpeming, located in the Northern Michigan University Archives would provide extensive detail on the varies occupations Cornishmen got involved in.

Women

The Upper Peninsula was a hard land, especially for women where the amenities of life were few. In the early 1850s Rebecca Jewell Francis was listed in the census. She had been given the Ojibwe name Swangideed Wayquay or Lady Unafraid because of her courage in braving the frontier and its notorious winters. Furthermore, she taught general education to the local Native American population.

A woman's traditional role was "to stay at home, keep house, and raise families." In the early days of Cornish settlement in Michigan, women had to improvise to adjust to the frontier conditions of the mining districts. Many married women had large families, so much of their time was spent on family chores such as washing laundry, making and repairing clothing, preparing food, and cooking meals.

There were few industrial outlets in the mining districts where women, even if they and their husbands were so inclined, could find employment. Some women found that they could bring in additional wages to their families by taking in boarders. Boarders were often close family relatives and it was not uncommon to have family squabbles add to the tension of living in close-crowded quarters. In 1860 a boarder was charged $10 per month or $120 per year, and in 1864 the price rose five dollars. If a boarding house served "Yankee style" food, the price often climbed to as much as $20-$25 per month.

Cornish woman found that if they were careful with their time they could find recreation outside the home. They would visit with family and neighbors and attend picnics in the summer. The Methodist church offered a variety of social organizations including the Ladies' Aid Society, temperance groups, or church choir. Minnie Uren, for example, was the church organist in Negaunee in 1905. In July 1903 the Ladies' Aid Society of Mitchell Methodist church in Negaunee gave a house social and lawn party. The event consisted of ice cream, cake, and an informal program of vocal and instrumental music. Outside the church, Daughters of St. George lodges, which were found in most Cornish communities, attracted many Cornish women. An auxiliary of the Sons of St. George, the Daughters provided labor for the Good Friday and St. George Day community dinners. Women were members of women's auxiliaries of the Masons and other feminine organizations.

Politics

Local and state politics attracted many Cornish immigrants. The early county records of the Copper Country and the three iron ranges show many Cornish immigrants serving in a variety of capacities as constables, supervisors, clerks, justices of the peace, education inspectors, and mine inspectors to mention a few. Later many would serve as mayors and city officials as well. Their children continued to serve in similar capacities. As an example, Peter W. Pasco was born in Porkellis, Cornwall, in 1854. He settled in Republic where he served as assistant superintendent until 1884 and then as underground captain for the Republic Iron Mining Company. Around 1903 he served as clerk of Republic Township and then for two years held the office of township treasurer.

Although he was not involved in Marquette County it is important to highlight Thomas B. Dunstan (1850-1902) from the Copper Country who went on to become lieutenant governor. He accompanied his parents from Camborne when he was three years old. He attended Lawrence University in Appleton, Wisconsin and the University of Michigan law school and was admitted to the bar in Keweenaw County in 1872. He was soon elected judge of probate and was prosecuting attorney for Keweenaw County. In 1879 he moved to Pontiac and returned to Central Mine in 1882. Soon after he was elected to the state legislature; he was a delegate to the Republican National Convention in Chicago in 1886, and was elected to the state senate in 1889. Dunstan was elected by a large majority as lieutenant governor (1896-1897); after his term he returned to his law practice in Hancock. Besides his political career, Dunstan was president and director of a number of mining companies and banks. He was also appointed to the Michigan Technological University Board of Trustees and was an active member of the Historical Society of Michigan.

Religion

During the eighteenth century, Cornwall was the scene of preaching by John Wesley (1703-1791), the father of Methodism, and many Cornish people were attracted to Methodism. Cornish immigrants brought a strong attachment to Methodism with them to the New World.

As a result, when Cornish people moved into an area or community, they soon established a Methodist church there. The adjacent towns of Phoenix and Central Mine are examples of this type of development. The village of Phoenix was established in 1843-1844 and a Methodist church was established soon after. It continued to hold services until the late 1920s. At Eagle Harbor a Cornish Methodist congregation was organized during the winter of 1846-1847, and as more Cornish people arrived new churches were opened. The Central Mine Methodist Episcopal church was opened in 1869 and was active until it closed in 1903. Still standing, its simple architectural style mirrors that which appeared in Cornwall in the fifteenth century.

Religion was an important part of the lives of the Cornish people. Many Cornish individuals preached at Sunday services and others became Methodist ministers, missionaries, and social workers. Reverend Frank Dye was born in 1875 in the Mark of Cornwall and in 1893 attended the Moody Bible Institute in Chicago. He first served a Congregational church in Iron Mountain and was known for his plain language sermons. During his fifty-year ministry he was a guest preacher at many seminaries, colleges, and universities. He eventually founded the Los Angeles Wilshire Boulevard Congregational Church.

Culinary Customs

The Cornish brought a number of foodways with them, but the Cornish pasty is the most identified with the Upper Peninsula and the Cornish immigrant. Legend has it that the Devil would never dare cross the River Tamar for fear of ending up as a filling in a Cornish pasty. Over the centuries a variety of ingredients have gone into the pasty crust.

The pasty is a hearty and nourishing food that miners took into the mines with them and warmed on a shovel over a candle. The American chronicler, John Forster wrote of the pasty. He said when the Cornishman went to dine he said, "I must take my meat," and warmed his coffee and pasty with the candle on his hat. Forster continued:

A 'paasty' is an enormous turn-over, filled with chopped beefsteak, boiled potatoes and onions with spice. This strong dish is immensely satisfying. It is the Cornishman's great backer, but no American should indulge in the toothsome 'paasty' at a late hour unless he should desire to have called up in his dreams, ghosts of his forefathers, in unlimited succession.

Though it is a relatively simple dish, there are heated debates over what constitutes a "traditional" pasty. This free-standing pie is usually composed of diced or ground beef, potatoes, and onions. The introduction of carrots and rutabagas remains controversial. Culinary writers Jane and Michael Stern talk about this controversy in Real American Food:

Serious gastro ethnographers distinguish between a true Upper Peninsula Cornish pasty, made with cubes of steak, and a Finnish-style UP pasty, made with ground beef and pork. Further debate swirls around issues such as whether the dough should be made with lard or suet; and the filling — with or without rutabaga; and the crimp of the crust — at the top or along the side edge.

The pasty was consumed not only by miners, but also by Cornish families as their main meal. Every Cornish housewife had her own special pasty recipe. The pasty remains popular in the Upper Peninsula today, and is still seen as a traditional Cornish-American food.

More than a century and a half after its introduction, the pasty has been accepted by many in the Upper Peninsula, and shops selling the pasty cane be found in the Lower Peninsula as well. Some people will argue with you that the pasty is actually a traditional Finnish food! Only in the Upper Peninsula can the designation "Pasty Shop" be found in the Yellow Pages. Pasties are sold fresh or frozen from pasty shops that dot the roadsides from Ironwood to St. Ignace. As with the many Upper Peninsula foods, it has become so popular with visitors that it is shipped throughout the United States as well.

The pasty was not the only food introduced by the Cornish. There was heavy cake, plum pudding, scalded or clotted cream, figgy duff, saffron bread or buns, and seedy biscuit. Many of these traditional foods continue to be eaten by third and fourth generation Cornish-Americans.

Sports

Cornish immigrants introduced a number of unique sports to Michigan. The game of cricket expanded in England in the eighteenth century and by 1773 was being played in Devon and also in neighboring Cornwall. This interest in cricket continued to spread and when the English and Cornish settled in the United States in the nineteenth century they introduced the game to Michigan. Cricket was first introduced in Detroit with the establishment of the Peninsula Cricket Club in 1858. They played on grounds located on Woodward Avenue. By 1885 its officers were primarily English in origin. Cricket was popular on the East Coast in the nineteenth century, and by 1890 there was a cricket league playing major East Coast and Midwest cities including Detroit.

Many of the Cornish who settled in the Upper Peninsula were skilled players and organized cricket teams especially in the Copper Country. On the Marquette Iron Range, on Saturday afternoon, July 16, 1892, the Sir Humphrey Davy Lodge of the Sons of St. George played a Marquette team and won by four wickets. Little is recorded of other cricket games, as baseball was becoming the sport of choice throughout the Upper Peninsula. However, the Cornish and other people of British origin played the game with which they were familiar. In 1908 there was talk of a cricket series between the English Oak and North of England teams along with eight teams in the Copper Country. A year later a cricket club was organized in Negaunee with the intention of league play with teams in the Copper Country from Calumet, Tamarack, Kearsarge, Ahmeek, Quincy, Mohawk, Trimountain, and Painesdale. Unfortunately little information about the local games appears in the Marquette Mining Journal due to the lack of popular interest. Cricket died out with World War I but around 1923 there was an attempt at reviving the game in the Copper Country. Today it is virtually an unknown sport in the United States.

Wrestling was an important facet of Cornish life and was described in detail in Richard Carew's survey of Cornwall in 1602. Due to work in the mines, the average Cornish miner developed a strong build. Bare-footed, the wrestler wore a special canvas jacket with a wide canvas belt tied firmly in front. The starting "holt" was a vice-like grip on the opponent's lapels—and from then on it was each man for himself.

Cornish wrestling tournaments were frequently held for Sons of St. George celebrations like St. George's day and the summer reunion. They were also held for the 4th of July and as exhibitions. The communities of Ahmeek in Houghton County and Negaunee in Marquette County had special facilities with bleachers for the grand exhibitions held there. At Ahmeek, which was a center of wrestling, there was seating for 2,000 spectators, and wrestling tournaments were held under the auspices of the Ahmeek Athletic Association. In 1916 they held some of the most successful tournaments in the Copper Country.

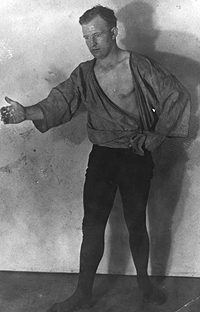

Cornish wrestling became so popular that men of other nationalities learned its techniques and competed. Some Cornish wrestler moved into regular wrestling. Jack Carkeek (1861-1924) who had started Cornish wrestling in 1877 in Michigamme by 1909 had a national reputation not only in Cornish wrestling but in catch-as-catch-can and Greco Roman styles. After trouble with the law in San Francisco, California, Carkeek dropped from the scene. Another sporting activity was hammer-and-drill contests. The contests were the pride of the ethnic group and held as part of the 4th of July celebration. Three-man teams from the various mines would pound away at huge blocks of rock. The team that could drill the deepest in a given period of time won a barrel of beer. There was such avid interest in hammer-and-drill contests that the Marquette Mining Journal published the results of the contests in Butte, Montana, where many Upper Peninsula Cornishmen migrated.

Cornish vs Other Nationalities

The Cornish came to the mining company speaking the English language and possessing expertise to work in the mines. As a result, they obtained the best positions in the mines, while others with fewer skills or late arrivals were forced to take lower positions. The Cornish also kept other immigrants from working their way into the mining hierarchy. The Irish, who went to the Copper Country in the early days of mining, also spoke English but did not have the same mining expertise as the Cornish. Religious differences between the Catholic Irish and the Methodist Cornish resulted violent clashes between these two Celtic people at times in the 1840s and 1850. Later on the Marquette Range many immigrants such as the Finns did not appreciate the Cornish and the fact that they held important jobs and decided whop received the best jobs in the mines and on the surface.

Cornish Dialect and Its Influences

The Celtic languages are split into two groups: Cornish, Welsh, Breton form one group with common roots, while Irish, Manx, and Scots Gaelic form a second group. The Cornish language was developed by a tribe called the Dumnonii who inhabited most of southwestern Britain. Here around 2000 BC, Cornish started to evolve as a separate language. An independent Cornish language continued until the eleventh century when English became the language needed to succeed. Eventually Cornish was looked upon as the language of the poor people. The church acted as a further stimulus for English, as the Prayer Book was only published in English. Eventually the last Cornish speaker, Dorothy Pentreath, died in 1777 near Mousehole although another story says that the last native Cornish speaker died around 1891 near St. Just in Penwith.

The Cornish people who came to Michigan spoke a dialect that was highly pronounced and differed from other English dialects. One of the distinctive elements was that the Cornish pronounced the "h" when it was not necessary before vowels like h'apple, h'oranges but dropped it when the it should have been in place as in 'ome, 'otel, and 'eart.

Besides their dialect the Cornish brought with them mining terms that were mostly old English words given a particular meaning. There were several hundred, many of which were in common usage. A few of these words are as follows:

a brave keenly lode: a fine lode of ore

bal: mine

deads: waste rock

grass captain: a surface boss

lode: a vein of ore (The terms is probably derived from the verb to lead)

skep or skip: the bucket-like receptacle in which ore is hoisted to the surface

sump: the place where water is collected in the mine

whim: the capstan used in raising ore for smaller operations

Other common terms used by Cornish people include, "to touch a pipe" meant to smoke, "a plod" meant a tale or story, "a passel of people" meant a lot of people, and "tuckered out," meant exhausted.

Cornish surnames follow prescribed forms. An old rhyme helps to explain this: By Tre, Ros, Car, Pol and Pen You may know all Cornishmen.

To best explain the prefixes: Tre means house, Ros means a heath, Car means a camp, Pol means a pool, and Pen refers to a headland.

Religious Customs

Christmas and Good Friday were the two most significant religious events on the Cornish calendar. When they settled in the Copper Country, Cornishmen spent the days before Christmas singing from house to house. Some people complained when some of them sang for ale, but this tradition continued for many years. At boardinghouses, Cornish women saw to it that Cornish boarders had access to an organ to sing and reminisce about Christmases past. Some of these men were so poor that all they remembered about Christmas were the hymns, as presents were never feasible. For some like Jim Collins, who grew up in extreme poverty, Christmas was like another Sabbath, but in the United States "it meant homecoming, a little added consideration in the family group, more warm heartedness between friends. It was a spirit easy to catch." In Highland Park in the 1920s, with the influx of many new immigrants, groups of Cornishmen went from house to house singing old Cornish carols to the delight of their countrymen.

Some of the miners provided special instructions to the children of the boardinghouse keeper. "W'y dawn't Santy visit more folks 'ere? The chimbleys be small and folks lock their doors. 'E dawn't carry keys, you know," said John Spargo, a miner who was introducing the boardinghouse missus' children to Santa Claus. Two weeks before Christmas a mine captain invited all of the English miners in the neighborhood to his home to sing carols to his homesick wife. About 30 men gathered and sang a couple of "currols" like "Hark! Hark!" and "Rule Britannia." Afterward the wife provided hot tea, raisin cookies, and saffron bread as well as seedy cake and a side of scalded cream.

Cornish miners sang Christmas carols as they were descending into the shaft. Once they reached the "plat" (working place), they were joined by the mining captains. The company spent a half hour singing carols before starting work. In 1920 Charles Miron introduced the underground Christmas celebration. A tree was brought down and carols sung. By the 1940s the music was directed by the Ishpeming high school music teacher, and "Genial Jim" Fowler, timber boss, dressed as Santa Claus and distributed gifts. Occasionally this celebration was broadcast via the local radio station. Groups of Cornish miners also broke into carols while having drinks in the local saloon much to surprise and amazement of out-of-town visitors.

Cornish miners and their families observed the Christmas holiday for three days: Christmas Eve, Christmas Day, and the third day, Boxing Day when they opened their presents.

Good Friday was an important day on the Cornish calendar. Women usually served their families fish; salted cod was common. The local Methodist church, under the auspices of the Sons and Daughters of St. George, in the Upper Peninsula would have a grand banquet and entertainment that raised funds for the church. This activity raised eyebrows among other religious adherents.

Music

The Cornish people love music. Fine choral singing was a staple in Methodist chapels, and John Wesley encouraged his followers to "sing lustily." This tradition was brought to Michigan and the Cornish became famous for their singing and especially for their traditional songs and Christmas carols. Miners sang walking to work and broke into a chorus as the man car took them to work in the lower levels. Rich natural baritone voices resonated on the bluffs around Central Mine. Pall bearers were heard singing "Nearer My Good to Thee" as they carried the coffin. Copper Country choruses regularly competed to determine which one was the best singing group.

In the mining communities, Cornish musicians either developed their own bands or joined city bands. The Sons of St. George lodges had the English Oak Band (Negaunee), which was a large cornet band, and Champion had the English Holly Band. These bands entered competitions and played at Cornish and non-Cornish events. When the English Oak band was disbanded, its members joined the Negaunee City band. The local bands throughout the Upper Peninsula were staffed principally by Cornish musicians.

Literature and Folklore

The Cornish immigrants did not have the time nor the energy to devote to writing. In later years men like have developed novels which relate to the Cornish experience in the Copper Country. Since they were English-speaking they did not have to develop their own newspapers as other ethnic groups did. However the local newspapers like the Portage Lake Mining Gazette (Houghton) and the Marquette Mining Journal would carry news of interests to the immigrants. From the earliest days the Upper Peninsula newspapers carried weekly columns of news from Cornwall, including prices of mine shares there, "carefully collated from [Cornish newspapers] giving the items of interest from the different towns for the benefit of our Cornish readers." Besides providing news from the Old Country the newspapers on a less formal basis provided news about Cornish residents in other parts of the United States especially in the western mining country.

Then there was folklore. Walter Gries (1892-1959), who lived in Ishpeming was an educator, civic-minded citizen and affiliated with the Cleveland Cliffs Iron Company. He was a folklorist of Cornish dialect stories that were used in folklore collections, especially those of Richard Dorson. In 1946, Dorson visited the Upper Peninsula and interviewed Gries and others and preserved a substantial body of Cornish stories. These were published in his work Bloodstoppers and Bearwalkers in 1952. Many of the tales which did not make the publication are available at the in the Dorson Papers in the Lilly Library of Indiana University-Bloomington.

The Cornish were fond of jokes, as their numerous dialect stories attest. Jokes sometimes took the form of practical jokes, which could be hard on a victim, but they were chiefly of a kindly nature. The Cornishmen are one of the few people who can enjoy jokes about their own peculiarity within their own company and never tire in telling them. "Cousin Jack" is the name given to stories of this type. A typical story follows:

A cross-eyed Cousin Jack at the Quincy [Mine] saw some large grapefruit in the window and thought they were oranges. He said, "It wouldn't take many of they to make a dozen." Told by James E. Fisher, Houghton, August 26, 1946.

Cornish immigrants and their culture and speech-patterns appear in Michigan literature. Two noted authors who write in this venue are Cornish-born Newton G. Thomas (b. 1878) and Michigan-born John D. Voelker (1903 -1991).

Thomas was born in Stokes, Cornwall and emigrated to Michigan's Upper Peninsula as a child. After growing up in these transplanted Cornish communities, he became a professor of dentistry and taught at Northwestern University Dental School, University of Illinois, and the College of Dentistry in Chicago.

He wrote the novel, The Long Winter Ends which was published in 1941. Using his first-hand experience, Thomas wrote about a year in the life of Jim Holman. The work looks at the trials and tribulations of this Cornish immigrant as he struggled to survive, maintain his heritage and ultimately be assimilated into American life.

John D. Voelker was the preeminent literary figure in the Upper Peninsula, with a well-honed ability to incorporate ethnic dialects into his work. In a sense Voelker goes beyond Thomas' focus. Many of his novels and short stories incorporate Cornish and Cornish-Americans illustrating how individuals and their culture and speech-patterns were incorporated into the life and times of northern Michigan in the twentieth century.

Cornish in the Wars

In all of the wars the United States fought in, Cornishmen participated. During the Civil War both recently arrived Cornish immigrants, Cornish-Americans and their sons served in the Union Army from Michigan. Stephen Cocking, a brigade bugler from the Upper Peninsula, served in the 23rd Michigan Volunteers. William Tresize came to the United States with his parents who first settled in Pennsylvania and then settled permanently in the Keweenaw and he worked in the mines until 1862. At that time he joined the 27th Michigan Volunteers and was wounded before Petersburg. Later, after returning from a mining stint in the West, Cocking became the lighthouse keeper at Copper Harbor. Cornish immigrants and Cornish-Americans who served heroically in the Spanish-American War, World War I, World War II, the Korean War, Vietnam War, the Gulf War and the War in Iraq.

Organizations

Cornish immigrants joined a variety of fraternal and benevolent organization soon after their arrival in Michigan. Freemasonry lodges were established soon after the Upper Peninsula was settled and Cornishmen became founding members of the lodges which developed. The lodge at Central Mine, a Cornish enclave, was instituted on January 8, 1868, and its membership was primarily Cornish. Individuals also belonged to the Odd Fellows, Knights of Pythias, Temple of Honor and Temperance, Foresters and later the Elks, the Eagles, American Legion and similar organizations.

The organization most closely associated with the Cornish people was the Order, Sons of St. George and its women's counterpart Order, Daughters of St. George. The national organization, named after St. George the patron of England, was established in Scranton, Pennsylvania in 1871. The order rapidly spread through the coal mining regions of Pennsylvania and adjacent states and across the country. In April 1887 the English Oak Lodge No. 230 was instituted in Negaunee. The first in the state of Michigan, it was soon followed by a lodge in Ishpeming, and in rapid succession lodges were established throughout the mining communities of the western Upper Peninsula. By 1910 there was a lodge in Detroit and another followed in Flint. Eventually there were hundreds of lodges scattered across the United States and Canada, and in 1906 membership in these lodges totaled more than 35,000. In the Upper Peninsula, the Sir Humphrey Davy Lodge in Ishpeming had the largest membership in the nation with more than 300 names on its rolls.

While nationally this fraternal secret society was composed of Englishmen, the Upper Peninsula lodges were dominated by Cornishmen. Membership was restricted to those eighteen to fifty years of age who were eligible for sickness and death benefits. Those over 50 years of age were given honorary membership. The lodges provided newly arrived immigrants the opportunity to fraternize with fellow countrymen and assimilate into American society. Some lodges like the English Oak of Negaunee and the English Holly of Champion had their own bands and others were large enough to invest in their own halls, which became revenue producers.

Besides holding frequent meetings, the society annually celebrated three important events: Good Friday, St. George's day (April 23), and the annual summer reunion. On Good Friday the order had a popular dinner and entertainment usually at the local Methodist church. On St. George's day and during the summer reunion, held for several days in July or August, lodge members traveled from afar and attended parades, business meetings, speeches, musical entertainment, Cornish wrestling, bicycle races, and band contests. These latter reunions allowed immigrants from throughout the region to visit friends and relatives. The order declined in the 1930s and is no longer in existence.

The Continuing Role of Cornish Communities in the Upper Peninsula

Although a relatively small ethnic group, the Cornish have insisted on maintaining their connection with Cornwall, American Cornish communities, and their heritage. Alfred Nicholls developed the Cornish reunion for former residents of Central Mine in the Copper Country. The first reunion was held in 1907 and continues to the present day. Once a time for former residents to visit and reminisce, it is now attended by fourth and fifth generations from throughout the region seeking a connection to their heritage. By 1915 the remaining Cornish folk in the Copper Country maintained good relations with their compatriots in places like Grass Valley, California, and Butte, Montana and this tradition continued with other communities in Michigan and surrounding states.

A number of institution have been organized to arrange reunions. Dorothy Sweet and Paul Liddicoat founded the Cornish American Heritage Society in 1982. Liddicoat was its first president. Although it started mainly as a genealogical organization, over the years it has grown more than 500 members and has expanded its focus to many aspects of Cornish heritage and culture. It is affiliated with many Cornish organizations that have developed in southwestern Wisconsin, the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, California and British Columbia, and Butte, Montana. Affiliated organizations in Michigan include Cornish Connection of Lower Michigan and Keweenaw Kernewek—Cornish Connection of the Copper Country.

The first "Gathering of Cornish Cousins" was held in suburban Detroit at Fenton in 1982 and continues to be held on a biennial basis at locations with strong Cornish ties. Since 1993 the Society has maintained a library of more than 400 books, pamphlets, journals, and journal articles.

Individual Cornish-Americans maintain their heritage in a variety of ways. Some make and consume pasties on a weekly basis and bake saffron buns. Some Lower Peninsula Cornish groups gather for a pasty luncheon around March 5, the feast day of St. Piran, Cornwall's and the tin miners' patron saint. Others visit Cornwall frequently and belong to Cornish groups like Cornwall Family History Society headquartered in Truro, Cornwall, or subscribe to Cornish World.

The Cornish have had an important impact on Michigan. The early arrivals played essential roles in the development of mines and quarries. As the mines decline in economic importance the Cornish migrated from the Upper Peninsula to southern Michigan where they found a variety of position in the automobile industry. They also strengthened the presence of the Methodist church in many areas of the state where they also played important roles in the temperance movement. Throughout the years Cornish people have played a variety of roles in community service and government. At the opening of the twenty-first century, Candice Miller, of the United States House of Representatives and the city clerk of Marquette, Norm Gruber, Jr. are both of Cornish background. President and CEO of Bay Cast in Bay City, Scott L. Holman, is a member of the Northern Michigan University Board of Trustees. The director of the Michigan Iron Industry Museum in Negaunee, Tom Friggens, indirectly continues his family's attachment to mining, while the retired director of the National Ski Hall of Fame is Ray Leverton.

The pasty has become an important part of the culinary lore of the Upper Peninsula, and saffron buns can be found in many shops throughout the region. While cricket never became a popular sport, Cornish wrestling evolved into mainstream U.S. wrestling. While this small group of immigrants is little known to many Americans, the Cornish and their proud heritage have left a indelible mark on the development of Michigan.