Finnish Immigrants on the Marquette Iron Range

By: Marcus C. Robyns, CA

General background leading to 1880

Following centuries of domination by Sweden and a series of wars in the eighteenth century, Finland became an autonomous “Grand Duchy” of the Russian empire in 1809. For much of the nineteenth century, traumatic and unstable economic and political conditions wracked Finland and led to large scale emigration to the United States. Chief among these were extreme rural poverty in the north of Finland, the growth of a social democratic movement, and Russian political repression.[1]

The initial primary motivation for emigration to the United States after 1860 was the growing impoverishment of the Finnish peasant. In 1865, Finland experienced a devastating famine that caused a 10 percent drop in population.[2] Following the famine, the number of landless tenant farmers grew rapidly with hired workers representing 56 percent of the rural population. Between 1870 and 1890, Helsinki’s population doubled as landless agricultural workers that could not afford to emigrate to the United States moved to the growing industrial areas of the south. By 1901, farm laborers represented 43 percent of all rural households and the landless had little hope of obtaining land. According to William Hoglund, “almost seventy percent of them each had less than twenty-two acres of cultivated land and over sixty percent were agricultural dependents. The rest included rural migrants who had worked in Finnish cities. Most were unmarried and between the ages of sixteen and thirty years.” [3] After 1890, the primary reason for immigration changed from the hope of obtaining land and starting a farm to “the desire to escape the growing unemployment and underemployment in Finnish industrial centers.”[4]

The collapse of the agricultural sector of the Finnish economy contributed to the development of a strong social democratic political movement. In the growing industrial cities of the south, such as Helsinki, socialist organizing and anti-Russian agitation grew rapidly.

The Finnish Labor Party promoted a sweeping social-democratic program that called for universal suffrage, the eight-hour day, and improved working conditions for industrial workers and landless agricultural laborers.[5] In 1903, the Labor Party changed its name to the Social Democratic Party and fours later grew to dominate the Parliament.

In response to the development of the Social Democratic Party and growing nationalism, in 1899 Tsar Nicolas II appointed General Nicholas Bobrikov as the new governor general of the Grand Duchy of Finland. Bobrikov, a Slavic nationalist, imposed a broad program of “Russification” upon Finland that sought to end the movement toward an independent state and incorporate the country more fully into the Russian empire. The Russification of Finland led to a nation-wide strike that was a catalyst for social reform. By 1907, Social Democrats controlled eighty of the two hundred seats in the new Finnish Parliament. This period of political and social upheaval resulted in the out flux of thousands of emigrants to the United States.[6]

The General Nature and Scope of Finnish Immigration to the Marquette Iron Range, 1880-1920

Finnish immigrants came to the Marquette Iron Range as early as the 1870s but did not begin arriving in large numbers until the 1880s.[7] By 1920, Finns formed the largest foreign born group in all the major mining counties in Michigan, except for Dickinson County on the Menominee Iron Range and the Mesabi Iron Range of Minnesota. Those immigrants arriving after 1880 tended to be more rural and conservative in their political orientation. Following the political and social upheaval after 1900, the essential character of the average Finnish immigrant changed and ushered in a second wave of immigration to the United States. [8] These new Finns came predominately from the more urban provinces of Turu-Pori and Uusimma, areas of Finland that were hotbeds of unionism and socialism. These immigrants were more proactive and sought to “modify their voiceless and powerless position with industrial society.”[9]

Although Finnish immigrants constituted the largest foreign born group on the Marquette Iron Range, the group began to experience a decline in numbers after the turn of the century. In 1900, Finns accounted for 39.8 percent of the total foreign born population of 14,923. Ten years later, this number dropped to 5,020 Finnish born immigrants or 28 percent of the total foreign born population of 17,934.[10] Regardless of the decline, Finns continued to outnumber other immigrant groups three to one. [11] Although the total number of Finnish born immigrants dropped again to 4,620 in 1920, the total population of foreign born also dropped to 13,887, making the percentage of Finns to foreign born actually increase to 33 percent.[12]

Finnish immigrants worked primarily as iron ore miners or in some capacity related to mining. In the 1910 census, Forty-seven percent (518) of the total number of Finnish residents of Ishpeming (1093) identified themselves as miners. Similarly, fifty-five percent (944) of the total number of Negaunee Finns (1713) worked as miners. By contrast, the next largest immigrant group, the English, identified themselves as miners 37 percent (390) in Ishpeming and 44 percent (326) in Negaunee.[13]

The demographic composition of Finnish immigration to the United States changed considerably over the period 1873-1913. In the early years, the majority of adult male immigrants were farmers 15.7 percent in 1873 as compared to 8.7 percent for adult male urban workers. Over the years, the number of urban workers among the immigrant population increased and the number of farmers decreased. By 1913, farmers represented only 4 percent and urban workers 24 percent. Early immigration came predominantly from the north and central regions of Finland after the turn of the century and then moved south from Oulu and Vaasa provinces to the southern and eastern parts of Finland.[14]

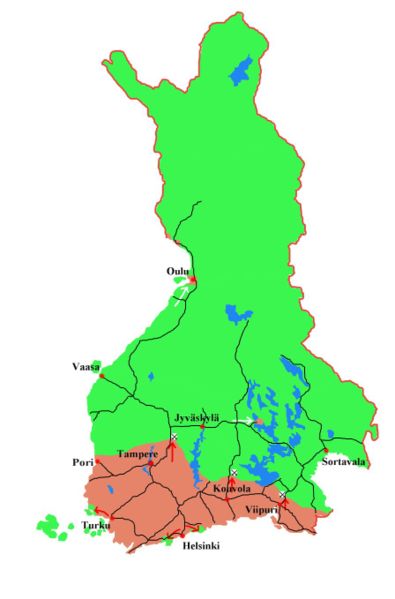

Surprisingly, analysis of naturalization records for Marquette County suggests that immigration after 1900 continued to come predominately from the rural central and northern regions of Finland. The southern, urban, and politically radical Finns appear to have by-passed the Marquette Iron Range for greater opportunities in Minnesota and elsewhere. In the first two decades of the twentieth century, eighty percent of the Finnish immigrants who applied for citizenship (550) from the green highlighted areas of Finland. [15]

Only 20 percent (138) arrived from southern Finland, highlighted in red. Of those from central and northern Finland, 43 percent (237) came from the province of Vaasa and 30 percent (160) from the province of Oulu. Of those from southern Finland, 51 percent (71) came from the city of Turku and 7 percent (10) came from the city of Hameenlinna; the remainder arrived from scattered towns and villages throughout the south. None are shown to have immigrated from Helsinki, Finland’s capital and largest city.[16]

The Lutheran Church

Finnish Lutherans were divided between followers of the Suomi Synod and the Laestadian – Apostolic Church. Suomi and Apostolic traditions grew out of revivalism in nineteenth century Finland. The Suomi Synod sought to replicate much of the Church of Finland in the Lake Superior country. The Synod stressed attendance at church services and meetings and financial support. Not spiritual awakening but preservation of a heritage was their primary concern.[17] These Lutherans were content with regular church attendance as “an end in itself” and constituted the great majority of Finnish Lutherans. Conversely, the Apostolic Lutherans “sought to reproduce on the American continent a church of true believers, meaning by that people who had entered through the door of personal absolution administered by a fellow believer.”[18] The constitution of the Suomi Synod was initially Episcopalian and authoritarian in nature. However, most parishioners in Michigan rejected this approach and wanted a less “clergy centered” organization. Consequently, the Synod modified its constitution but retained the power of the clergy through the consistory, an executive authority with a direct voice in the administration of church institutions, the power to adjudicate disputes, and approval of candidates for the ministry.[19]

Laestadians were not a cohesive group and doctrinal differences often blocked efforts at unity within the group. These differences also made reconciliation with Synod Lutherans nearly impossible. Laestadians tended to emphasize conviction of sin under the law, while the Synod found redemption through the gospel of Christ. On the Marquette Iron Range, Laestadians were known as “holy-jumpers” because of their charismatic preaching and spirit-filled worship services.[20] The Synod followed a much more conservative and moderate approach to the gospel, sustained by a learned clergy and committed to a lifetime of growth Christian doctrine: “Laestadians envisioned the Body of Christ to be composed of regenerate believers whereas Synod Lutherans, most notably Nikander, allowed for gradations of commitment in the gathered community of faith.”[21]

The Suomi Synod was well-established and dominated Finnish religious life on the Marquette Iron Range. Indeed, Finns on the Range played a prominent role in the formation of the Synod. In 1889, Ishpeming was one of three communities in the Lake Superior district to host a series of Suomi Synod mission festivals.[22] Kaarlo Tolonen, the pastor of the Ishpeming congregation, participated in the formation of the Consistory in Hancock, Michigan, on December 17, 1889. John Jasberg of Ishpeming was a prominent businessman who participated in the first constituting convention on March 25, 1890. He was also an organizer of the Finnish Lutheran Book Concern and business manager of Suomi College. Other prominent business leaders from the Marquette Iron Range included Karl Sillberg of Republic, and Niilo Majhannu of Ishpeming. These delegates “represented a traditionalist, conservative element in the immigrant population, and were inclined to favor a paternalistic church and clergy.”[23] In effect, the convention was dominated by the clergy, the businessmen, and the conservative journalists and editors.”[24]

Membership in the Suomi Synod Lutheran Church on the Marquette Iron Range was consistently twice as high as the membership on the Mesabi Iron Range. The only towns on the Mesabi to consistently report church membership were Chisholm, Duluth, Ely, Eveleth, and Mountain Iron. The towns on the Marquette Iron Range with the highest church membership were Ishpeming, Negaunee, Republic, and Champion. Church membership in these communities was 2,284 in 1910 or 45 percent of the Finnish born population (5,020) in Marquette County. Ten years later membership rose 31 percent to 2,994 or 65 percent of the Finnish born population.[25]

The Socialist Party

As noted earlier, most Finns that came to the Marquette Iron Range tended to be socially and politically conservative. Still, significant number of educated and experienced in the socialist and radical labor movements did arrive after 1900.[26] In 1905, the Socialist Party of Michigan chartered the Finnish Branch of the Socialist Party in Negaunee. The following year, the group affiliated with the newly formed Finnish Socialist Federation and attempted to launch a socialist newspaper on the Range.[27] The Branch grew slowly, and by 1913 the group could only claimed a membership of 160. The Ishpeming Iron Ore noted the modest size of the Finnish Socialist Federation (FSF) and suggested that the local Finns had managed not to be “duped” by the socialists and wobblies as their more unfortunate brethren on the Mesabi Iron Range.[28]

The Socialist Party on the Range was, at best, a marginal political organization and did not reflect the Socialist Movement’s national or regional strength, particularly in urban areas with populations over 10,000. Despite running a candidate for every partisan office in Marquette County between 1908 and 1914, the Socialists were never able to poll more than 600 votes. The only exception occurred in 1912 when Thomas Clayton, Socialist Party candidate for Inspector of Mines, received 1,216 votes, or 19 percent of the total. Martin Skauge, Socialist Party candidate for Register of Deeds, received the next highest vote tally with 583, or 9 percent of the total votes cast. And William Ronback, candidate for Michigan First District state representative, garnered the fewest votes with only 195, or 6 percent of the total. In 1914, the Marquette County Socialist Party entered its last full slate of candidates for county-wide elections and first district state representative. The results were equally dismal, with no candidate receiving more than 250 votes. Frank Vivian, candidate for County Coroner, received the most with 237 votes or a paltry 1.7 percent of the total. The Marquette County Socialist Party never again ran a candidate for county-wide elected office.[29]

The Party’s poor showing at the polls was partly a reflection of destructive factionalism that weakened its ability to provide effective leadership and a unified front. This factional conflict mirrored the concurrent debate among national and regional organizations over the question of whether or not to follow a program of parliamentarianism or anarcho-syndicalism.[30] The conflict on the Marquette Iron Range erupted over control of the Negaunee Labor Temple, the focal point of socialist and radical labor activity on the Range. Despite its small membership, the FSF managed to build a major labor hall in Negaunee in 1910[31] The Negaunee Labor Temple was an impressive Victorian style structure and boasted plush seats and a large stage. The Temple was more than just a meeting place and provided a diverse array of services, such as solace to the lonely, doctrinaire education, entertainment, and even helped with naturalization process.[32]

The two competing factions within the socialist movement on the Marquette Iron Range were led by two seasoned veterans. Frank Aaltonen led the parliamentarian socialists.[33] He worked as an organizer for the Negaunee Miners Union, Local 128, a local affiliated with the Western Federation of Miners, and was one of the WFM’s principle organizers during the catastrophic 1913 Copper Country strike. Aaltonen’s nemesis and challenger was William Nilssen Risto, a Finnish immigrant of Swedish origin and the leader of the anarcho-syndicalist faction. Risto was an avowed syndicalist and hardcore socialist agitator. He was born on September 16, 1882 and immigrated to the United States in 1903. No record exists of Risto ever having naturalized as citizen, and he never ran for elected office in Marquette County. Risto went on to settle in Negaunee, where he raised a family and worked for the City of Negaunee until his death in 1962.

Risto was a fiery proselytizer of anarcho-syndicalism, and his aggressive advocacy eventually got him fired as a Socialist Party organizer on the east coast. He described industrial sabotage as a “Doctrine of Struggle” and likened it to a “strike on the job.” Risto called this approach “intelligent sabotage” and thought it to be far more effective than an actual strike. At the same time, he saw political action within the electoral process as pointless, because “the Bourgeoisie class control the political process and representation in Congress and state legislatures.”[34]

As the director of the Negaunee Labor Temple, Risto spent much of his time proselytizing idle workers to the doctrine of anarcho-syndicalism and succeeded in gaining a significant following. In 1913, he allegedly withheld some votes cast during the state Socialist Party election. Risto claimed that the ballots had become lost and that replacement ballots from Ishpeming had arrived too late to send on to state headquarters for consideration.[35] The Aaltonen faction, recognizing the growing threat posed by Risto, immediately seized upon this failure and accused him of criminal intent. Aaltonen submitted an official complaint with the Michigan State Socialist Party and also filed for a court injunction against the Risto faction in Marquette County Court. Following a controversial visit and investigation, the State party secretary revoked the local’s charter and ordered the reformation of the Negaunee FSF under Frank Aaltonen’s leadership.[36] Risto’s faction refused to give-up and locked the Aaltonen group out of the Temple. Aaltonen eventually secured a court injunction against the Risto faction, kicking them out of the temple and forcing them to turn over all records, funds, and property.[37]

The Temperance and Cooperative Movements

The Finnish Cooperative Movement began roughly the same time that character of immigration to the United States shift towards a more radical, socialist perspective. Finns used consumer food cooperatives as a way to challenge the commercial monopolies and company stores. Members co-owned the stores and enjoyed substantial discount in grocery prices. By 1917, Finnish immigrants had established 23 cooperatives throughout the United States but predominately in the Great Lakes region. The first cooperative opened in 1903 in Minnesota, and the first on the Marquette Iron Range opened in 1907 in Republic.[38] Between 1916 and 1919, cooperatives opened in Negaunee, Ishpeming, and Marquette. All three cooperatives aligned themselves with the Socialist Party, with members of the Ishpeming store referring to it as “a laborers’ store, run by laborers for laborers.” Indeed, in 1916 the Finnish American Cooperative Union forms as the national umbrella organization officially affiliated with the Socialist Party.

As the Cooperative Movement grew into the 1920s, more conservative Finns began to challenge the Socialists’ control. Many resented the Socialist Party’s call for the use of Cooperative profits in socialist education and agitation activities. The struggle accelerated during the Great Depression when the American Communist Party (CPA) began to agitate for control of the cooperative movement. In Eben, Michigan, the cooperative came under direct communist control and was known as “Unity Co-op.” In 1932, the group eventually split from the Central Wholesale (Farmers) Cooperative. The split occurred because communist members wanted to begin sending relief money to Russia. Although the CPA continued to influence Cooperatives throughout the region, the group failed in its attempt to dominate the movement and finally gave up in 1936.[39]

The consumption of alcohol was a prevalent part of Finnish social behavior for much of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Because of the widespread dysfunction caused to families and communities from alcohol abuse, Finnish immigrants very quickly formed temperance organizations upon arrival in the United States to combat the problem. Finnish temperance organizations sought to restrict alcohol abuse through education, by providing alternative social activities and amusements, and by actively promoting legislation to regulate alcohol production and consumption.

The Finns on the Marquette Iron Range took the lead in the Temperance Movement. The first organization formed in Republic in 1885 and was quickly followed by the Ishpeming Temperance Society in 1886. In 1888, temperance organizations throughout the Upper Peninsula met in Republic and formed the Finnish National Temperance Brotherhood of North America.[40] These organizations were politically very conservative, closely aligned with the Lutheran Church, and vehemently anti-socialist. In fact, Temperance societies on the Range very actively worked to oppose the Socialist Party and radical labor groups. By 1906, the Finnish temperance movement on the Marquette Iron Range actively joined the national effort for Prohibition. In 1908, all the groups on the Range met in Ishpeming and formed the Marquette County Temperance League. This group ran candidates for local political office from 1908 through 1920 but never garnered more than 2-3 percent of the vote.[41]